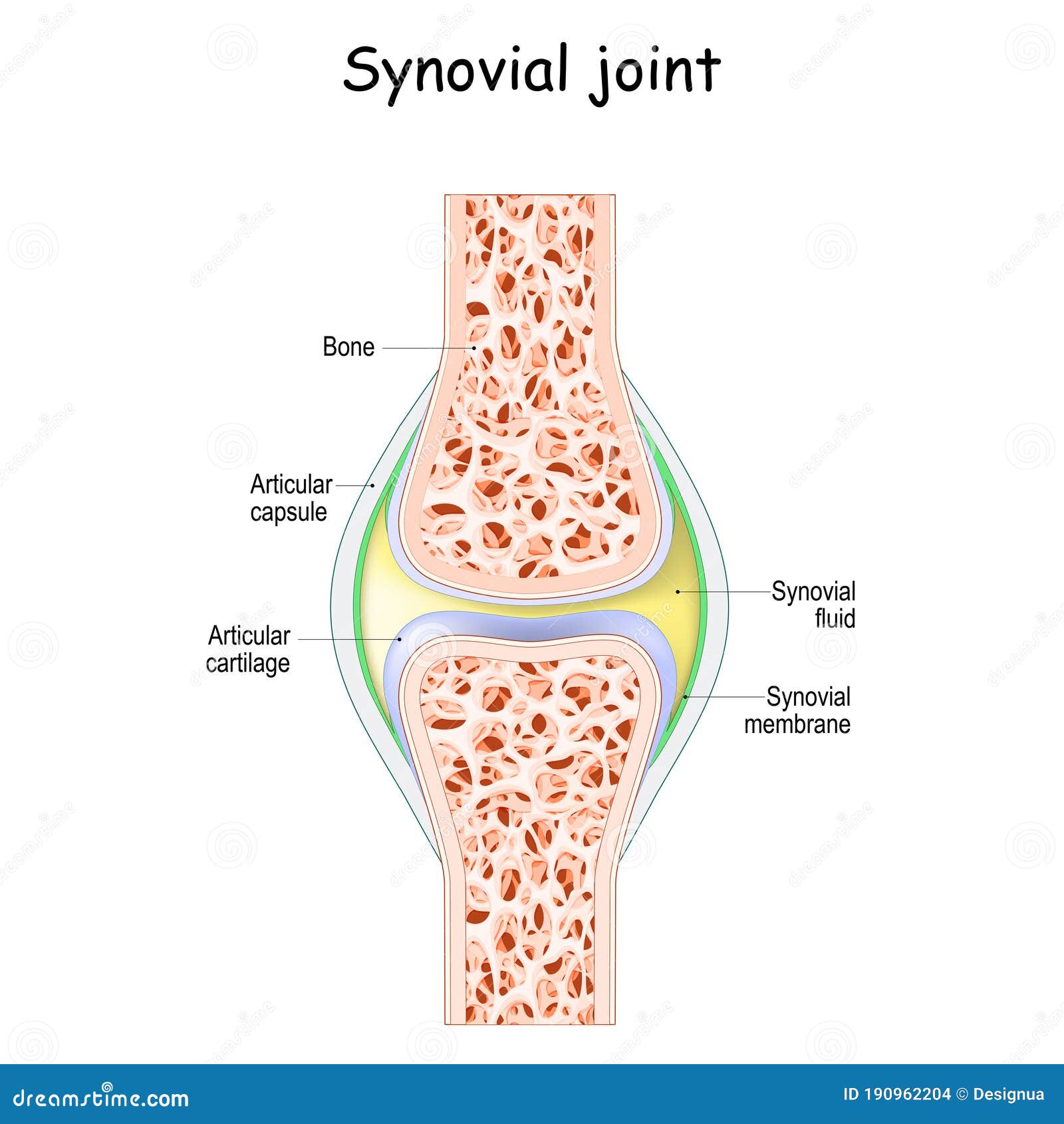

A synovial joint, also known as diarthrosis, joins bones or cartilage with a fibrous joint capsule that is continuous with the periosteum of the joined bones, constitutes the outer boundary of a synovial cavity, and surrounds the bones' articulating surfaces. This joint unites long bones and permits free bone movement and greater mobility. The synovial cavity/joint is filled with synovial fluid. The joint capsule is made up of an outer layer of fibrous membrane, which keeps the bones together structurally, and an inner layer, the synovial membrane, which seals in the synovial fluid.

They are the most common and most movable type of joint in the body of a mammal. As with most other joints, synovial joints achieve movement at the point of contact of the articulating bones.

Structure

Synovial joints contain the following structures:

- Synovial cavity: all diarthroses have the characteristic space between the bones that is filled with synovial fluid.

- Joint capsule: the fibrous capsule, continuous with the periosteum of articulating bones, surrounds the diarthrosis and unites the articulating bones; the joint capsule consists of two layers - (1) the outer fibrous membrane that may contain ligaments and (2) the inner synovial membrane that secretes the lubricating, shock absorbing, and joint-nourishing synovial fluid; the joint capsule is highly innervated, but without blood and lymph vessels, and receives nutrition from the surrounding blood supply via either diffusion (slow), or via convection (fast, more efficient), induced through exercise.

- Articular cartilage: the bones of a synovial joint are covered by a layer of hyaline cartilage that lines the epiphyses of the joint end of the bone with a smooth, slippery surface that prevents adhesion; articular cartilage functions to absorb shock and reduce friction during movement.

Many, but not all, synovial joints also contain additional structures:

- Articular discs or menisci - the fibrocartilage pads between opposing surfaces in a joint

- Articular fat pads - adipose tissue pads that protect the articular cartilage, as seen in the infrapatellar fat pad in the knee

- Tendons - cords of dense regular connective tissue composed of parallel bundles of collagen fibers

- Accessory ligaments (extracapsular and intracapsular) - the fibers of some fibrous membranes are arranged in parallel bundles of dense regular connective tissue that are highly adapted for resisting strains to prevent extreme movements that may damage the articulation

- Bursae - sac-like structures that are situated strategically to alleviate friction in some joints (shoulder and knee) that are filled with fluid similar to synovial fluid

The bone surrounding the joint on the proximal side is sometimes called the plafond (French word for ceiling), especially in the talocrural joint. Damage to this structure is referred to as a Gosselin fracture.

Blood supply

The blood supply of a synovial joint is derived from the arteries sharing in the anastomosis around the joint.

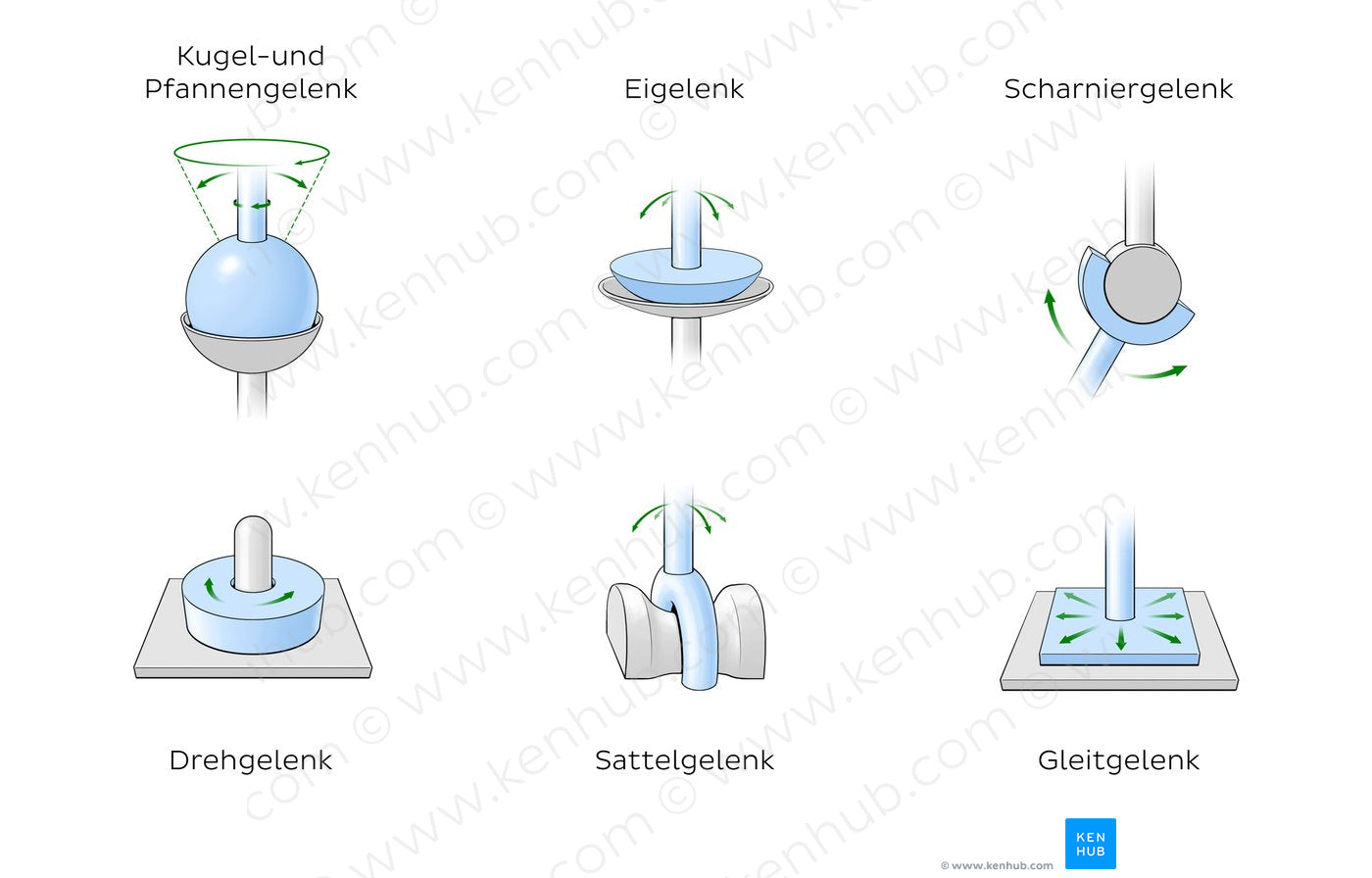

Types

There are seven types of synovial joints. Some are relatively immobile, therefore more stable. Others have multiple degrees of freedom, but at the expense of greater risk of injury. In ascending order of mobility, they are:

Multiaxial joints

A multiaxial joint (polyaxial joint or triaxial joint) is a synovial joint that allows for several directions of movement. In the human body, the shoulder and hip joints are multiaxial joints. They allow the upper or lower limb to move in an anterior-posterior direction and a medial-lateral direction. In addition, the limb can also be rotated around its long axis. This third movement results in rotation of the limb so that its anterior surface is moved either toward or away from the midline of the body.

Function

The movements possible with synovial joints are:

- abduction: movement away from the mid-line of the body

- adduction: movement toward the mid-line of the body

- extension: straightening limbs at a joint

- flexion: bending the limbs at a joint

- rotation: a circular movement around a fixed point

Clinical significance

The joint space equals the distance between the involved bones of the joint. A joint space narrowing is a sign of either (or both) osteoarthritis and inflammatory degeneration. The normal joint space is at least 2 mm in the hip (at the superior acetabulum), at least 3 mm in the knee, and 4–5 mm in the shoulder joint. For the temporomandibular joint, a joint space of between 1.5 and 4 mm is regarded as normal. Joint space narrowing is therefore a component of several radiographic classifications of osteoarthritis.

In rheumatoid arthritis, the clinical manifestations are primarily synovial inflammation and joint damage. The fibroblast-like synoviocytes, highly specialized mesenchymal cells found in the synovial membrane, have an active and prominent role in the pathogenic processes in the rheumatic joints. Therapies that target these cells are emerging as promising therapeutic tools, raising hope for future applications in rheumatoid arthritis.

References

Sources

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Text taken from Anatomy and Physiology, J. Gordon Betts et al, Openstax.